Substance Over Form

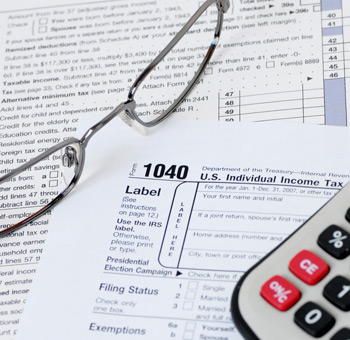

The burden is on the taxpayer to find the opportunities, interpret the Code, adapt his or her behavior accordingly and finally file the appropriate forms with the IRS.

The burden is on the taxpayer to find the opportunities, interpret the Code, adapt his or her behavior accordingly and finally file the appropriate forms with the IRS.

The Internal Revenue Service recognizes that taxpayers have the right to arrange their affairs to minimize tax liability. Lawmakers create tax opportunities within the Internal Revenue Code (the Code) for several reasons including the stimulation of the economy through business owners. However, the burden is on the taxpayer to find the opportunities, interpret the Code, adapt his or her behavior accordingly and finally file the appropriate forms with the IRS. With the Code’s insurmountable number of pages to comb through, along with the accompanying Revenue Rulings, many taxpayers turn to educated tax professionals to identify the tax opportunities applicable to their particular situations. Other taxpayers attempt to take tax planning into their own hands and they do so without the required knowledge of tax law. Not only does tax planning require technical compliance with the Code, but also the transaction’s form must be consistent with its substance.

The IRS may challenge a transaction before the final decision maker, the court, by asserting that the substance of a transaction does not match its form. In this case, a court may ignore the transaction’s form and levy taxes based on the transaction’s substance. Consider the following example: a wholly-owned corporation loans its shareholder $500,000. The shareholder issues the corporation a note. If this transaction’s only motivation and result is to create a tax benefit (avoiding income tax on the amount of the loan), the court can ignore the transaction as reported by the taxpayer. Instead, the court could determine that the loan to the shareholder was actually a dividend or a distribution and levy taxes based on that conclusion. The court applies one or more court-established tests, referred to as judicial doctrines, to determine whether the substance or the form should preside.

WHAT IS THE PURPOSE OF THE JUDICIAL DOCTRINES?

In tax law, judicial doctrines have been created by the courts to uphold the integrity of the Code. It would be impossible for lawmakers to foresee and address every situation and business transaction that could arise. Very often, abusive transactions fall right outside of the Code’s clear language. In contrast, some transactions comply with the technical language of the Code, but do not advance the purpose of the Code provision at issue. The IRS utilizes the judicial doctrines to challenge transactions where the language of the Code does not directly address a situation, or where a situation is directly addressed, but results in a transaction that does not comply with the purpose of the statute even when mechanically followed.

HOW AND WHEN DID JUDICIAL DOCTRINES COME ABOUT?

The Supreme Court first legitimized the substance over form doctrine in the landmark case Gregory v. Helvering. Gregory v. Helvering, 293 U.S. 465 (1935). A synopsis of this case highlights the application of the substance over form doctrine. Here, the taxpayer owned all the shares of corporation X. X owned some shares of corporation Y. The taxpayer desired to sell the shares of Y for a large profit. If done directly, there would be two levels of taxation. X would pay tax on the sale of Y’s shares, and the taxpayer would pay dividend tax when the profit from the sale was distributed to her.

In an effort to reduce her tax obligation, the taxpayer created a new corporation, Z. Z issued all of its shares to the taxpayer. The taxpayer caused the shares of Y to be transferred from X to Z. The taxpayer dissolved Z, and the shares of Y were distributed to the taxpayer as a liquidating dividend. Under the corporate liquidation laws in effect at that time, the shares of Y passed to the taxpayer tax-free. The taxpayer then sold the shares of Y and reported a capital gain. The taxpayer asserted that Y’s transfer of shares from X to Z was exempt from tax as gain from distribution in pursuance of reorganization under the Code.

The IRS assessed a tax deficiency on the basis that the reorganization was not a true reorganization within the Code’s meaning. The question before the court was whether the substance’s transaction or form should determine the tax liability. The substance of the transaction was X’s sale of Y’s shares and a subsequent distribution of the profit to the taxpayer. The form was a corporate reorganization resulting in the tax- free distribution of Y’s shares from X to Z. The Supreme Court affirmed the decision of the Court of Appeals and disregarded the reorganization, even though it was conducted according to the terms of the Code.

WHAT ARE THE JUDICIAL DOCTRINES?

Three judicial doctrines commonly invoked by the IRS to invalidate tax schemes are the economic substance doctrine, the business purpose doctrine and the step transaction doctrine. All three of these doctrines are utilized by the IRS to determine substance over form. Each of these will be explained following.

Economic substance doctrine

The economic substance doctrine is a twoprong test. A transaction has economic substance if: 1) the transaction is related to a business purpose, and 2) the transaction enhances the net economic position of the taxpayer (other than reducing tax liability). The former component is subjective and looks to the motivation behind the transaction. The latter is objective. Courts examine the latter requirement in different ways, most commonly, they examine whether there is a legitimate potential for pre-tax profit and whether a reasonable businessman would participate in the investment. Some courts require that both the business purpose and the economic substance portions of the economic substance doctrine be satisfied, while other courts require that only one of the two portions be satisfied.

Business purpose doctrine

The business purpose doctrine sets forth the requirement that a transaction be driven by some business consideration other than the reduction of tax. To determine the intent of the taxpayer, many factors have been considered by the courts, including: 1) whether the taxpayer had profit potential, 2) whether the taxpayer cited a non-tax business reason for entering into the transaction, 3) whether the taxpayer considered the market risk of the transaction, 4) whether the taxpayer funded the transaction with its own capital, 5) whether the entities involved in the transaction were entities separate and apart from the taxpayer, 6) whether the entities involved in the transaction engaged in legitimate business before and after the transaction and 7) whether the steps leading up to the transaction were engaged at arms-length. Remarks of Donald L. Korb, Chief Counsel for the Internal Revenue Service, California, January 25, 2005.

Step transaction doctrine

The step transaction doctrine applies to multi-step transactions. Under this doctrine, “interrelated yet formally distinct steps in an integrated transaction may not be considered independently of the overall transaction.” Commissioner v. Clark, 489 U.S. 726 (1989). Courts apply one (or more) of the following three tests to ascertain whether transactions are integrated for tax purposes: the binding commitment test, the mutual independence test or the end result test. The binding commitment test asks if, at the time of the first transaction, there existed a binding commitment to commence the second transaction. The mutual interdependence test focuses on the relationship between the steps and asks whether the success of one step depends on the success of the series of steps. The end result test asks whether a series of transactions are actually steps of a larger, overall transaction designed to meet a final result.

HOW DOES THIS APPLY TO YOUR BUSINESS?

A transaction does not trigger the application of the judicial doctrines merely because it was entered into with a desire to avoid tax. However, in addition to a tax avoidance motivation, business owners must also have a business motivation and the transaction must have some economic impact on the taxpayer. As in Gregory v. Helvering, the IRS can invalidate the creation of a business entity because it was created with the sole desire to avoid tax.

Before entering into a transaction, business owners should evaluate their transactions both objectively and subjectively. First, look at the applicable Code sections and ask the following: Am I meeting all the requirements of the Code? Is this transaction properly documented? Is the transaction properly and timely filed? In addition to these questions, business owners should ask: What is the purpose of the applicable Code provision? Does my intended transaction violate the purpose of the Code provision? Other than reducing my taxes, does this transaction have any economic impact on my business? What legitimate business motivations can I assert if this transaction is challenged?

Compliance with the Code’s technical requirements is critical as the IRS challenges the vast majority of transactions on compliance shortfalls, and these are the simplest arguments for the IRS to win. The judicial doctrines come into play only in a small percentage of cases – usually when the taxpayer thinks he or she has found a loophole in the Code and has finally outsmarted the IRS. Business owners and their tax professionals must know the judicial doctrines and when they apply before entering into a transaction. Once a transaction has occurred, it may be too late.